Using the regression methodology of Ray Fair ("The Effect of Economic Events on Votes for President," The Review of Economics and Statistics, May 1978), I estimate a 51.78% Obama vote share in the Obama-Romney race.

The election should be close, but Obama will probably be re-elected (note that Obama won 52.33% of the vote in 2008).

Another Unique Perspective

Thoughts about risk, insurance, terrorism, disasters, public policy, and other things that interest me

Friday, October 26, 2012

Monday, July 30, 2012

"Science through its physical and technological consequences is now determining the relations between human beings. If it is incapable of developing moral techniques which will also determine these relations, the split in modern culture goes so deep that not only democracy but all civilized values are doomed. A culture that permits science to destroy traditional values but which distrusts its power to create new ones is a culture which is destroying itself."

John Dewey

Saturday, July 14, 2012

The Sky is Pink

The highlighted video link opens an interesting video about the risks of hydraulic fracturing in New York State. See The Sky is Pink Video Link .

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Infrastructure Development - Where to Begin

For a government, its businesses, other organizations, and citizens to flourish, its people, goods, and information must have the ability to move and interact freely in an integrated, cost efficient, resilient, and effective manner. Reliable, responsive infrastructure helps make this possible. Infrastructure includes the physical structure, components, and systems that provide the energy generation, transmission, and distribution, transportation network, digital communications network, water treatment and distribution, wastewater treatment, flood control, solid waste disposal, and educational function of the government’s territory. Determining the proper mix of infrastructure investment by type and cost to be provided by government within its jurisdiction requires careful consideration and analysis of a significant amount of information.

Typical U.S. local elected officials[1] should acknowledge that much of their constituencies’ infrastructure—its roads, sidewalks, streetlights, bridges, dams, public schools and colleges, public hospitals, the electrical grid, the water system, the storm water system, the sewage system, and many other major societal support systems—have been neglected for far too long. In order to address this neglect, they should seek to invest in revamping most of the old and constructing some new infrastructure in their communities. First, they should inventory the current infrastructure in their jurisdictions, assess its scope and extent, and catalogue the histories and timelines of its construction, maintenance, and operation, including each system’s direct and indirect costs. Next, they should categorize their jurisdictions' infrastructure wants and needs based on (1) these current inventories and their current providers (i.e., private sector, my jurisdiction, or another (special district or differing level) jurisdiction), (2) the current and projected adequacy (or inadequacy) of this infrastructure to meet expected needs, (3) the current states of repair and remaining expected lives of this infrastructure, (4) the current and expected future unmet infrastructure wants and needs (based on historic failures, internally anticipated inadequacies, and surveys of the constituency), (5) the current and projected funding sources[2] (and its adequacy or inadequacy) for current and anticipated infrastructure that includes planning, construction, maintenance, and operation over the full life-cycle, and (6) special considerations such as zoning and other laws and regulations, environmental concerns and constraints, and public safety issues.

Once this information is collected, they should work with other elected officials to rank potential infrastructure investment based on a combination of societal need, public safety, sustainability, public desire, and life-cycle funding source adequacy, respectively.

[1] Since much of American infrastructure is built and operated by local or state governments, state or local officials are the main intial drivers of infrastructure development.

[2] These may include direct taxes, user fees, grants, bonds, private-public partnerships, or combinations thereof.

Related articles

- Infrastructure Spending Would Drive Growth (blogs.forbes.com)

- Budget woes encumber infrastructure (politico.com)

Thursday, April 28, 2011

Social Security and Public Infrastructure Investment

Currently and by law, income to the Social Security Trust Fund must be invested, on a daily basis, in securities guaranteed as to both principal and interest by the Federal government. All securities held by the Trust Fund are nonmarketable “special issues” of the United States Treasury. Such securities are available only to the Trust Funds.[1] However, there is some debate as to whether the current form of the Trust Fund is national savings or an accounting fiction.

As an alternative to the status quo, economically targeted public infrastructure investment, for example, using the Social Security Trust Fund (or, at least, a portion of it) for building or revamping infrastructure may be preferable to “special issue” savings. While there is some risk involved in infrastructure (What happens if it’s built and not used? What happens if there are considerable unplanned cost overruns, or what happens if operating and maintenance expenses exceed initial expectations (tied to revenues)?), this type of investment could serve as a substitute for some taxation as well as economic stimulus in its own right.

Elements to be Considered with Respect to Investing the Social Security Trust Fund in America’s Infrastructure

[1] In the past, the Trust Fund has invested in marketable Treasury securities. Marketable securities are subject to the forces of the open market and may suffer a loss, or enjoy a gain, if sold before maturity.

Saturday, April 9, 2011

Hydraq, a Trojan Back-Door Remote Controller

Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia |

| Trojan Horse |

This video from the Symantec Security Response blog shows how hydraq works:

Posted by

Unknown

at

Saturday, April 09, 2011

Labels:

Internet security,

Malware,

Security,

Trojan Horses

0

Comments

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaRelated articles

- IAEA Japan Nuclear Radiation Simulation & Wind Forecast Map (judydudiak.wordpress.com)

Friday, April 8, 2011

Stuxnet, the first true Cyber-weapon targeting Infrastructure

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia |

| Basic SCADA |

Win32/Stuxnet is almost certainly the most sophisticated virus yet developed for targeted attacks. Stuxnet is parasite code that focuses on subverting SCADA systems, the automated monitoring and control systems of many modern manufacturing, production, power generation, transmission and distribution, fabrication, water treatment and distribution, wastewater collection and treatment, oil and gas refining and transmission, and communication systems. Many SCADA software vulnerabilities can potentially be exploited by Stuxnet. All current and future efforts to secure infrastructure must now adapt to and address this potential new mode of attack on our infrastructure.

Related articles

- Cracking Stuxnet, a 21st-century cyber weapon [Greg Laden's Blog] (scienceblogs.com)

- Yet more on Win32/Stuxnet (eset.com)

- Stuxnet Evolves: (warintel.blogspot.com)

- Stuxnet, SCADA and malware (eset.com)

Posted by

Unknown

at

Friday, April 08, 2011

Labels:

Control system,

Programmable logic controller,

SCADA,

Security,

Stuxnet

0

Comments

Wednesday, April 6, 2011

Shirky's Here Comes Everybody

Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia |

Clay Shirky |

The Internet and Web 2.0, in particular, are revolutionizing how nonprofits can organize. High-speed grassroots activism and ultra-quick publishing methods are transforming the possibilities, speed, and impact of nonprofit activities. Clay Shirky explores the merger of the Internet’s promise, some new and effective tools, and an emerging, new type of market in his readable, interesting book, Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations (Penguin, 2009).

Image by k-ideas via Flickr Image by k-ideas via Flickr |

Ronald Coase |

In 1937, economist Ronald Coase considered the questions, “Why do organizations exist? and Why not just buy and sell individual services and goods in an open market?” Coase answered, that, in markets, there are transaction costs—these are the extra costs that buyers and sellers incur in order to meet one another and to negotiate. The Coase theorem states that, if transaction costs are low enough, direct markets of individuals make sense. But, if these costs are too high, it makes more sense to organize in order to seek economies of scale.

A corollary concept is Coase’s ceiling, the point above which organizations collapse under their own bureaucratic weight.

Shirky identifies a new market, the Coasean floor, a place wherein activities and markets whose value may not be worth the organizational transaction costs of performing them via the traditional marketplace may occur. These are the types of things suited for Internet activities. When organizational costs are close to zero and where ad hoc, loosely connected groups can form, many other possibilities, including nonprofit opportunities, emerge. The future may find more self-organization lacking formal hierarchies. Such “nonorganizations” would allow for contributions from a wider group of people. The aggregation of millions of actions that were previously below the Coasean floor have enormous potential.

There are potential problems, though. These involve people making poor choices of groups, for examples, teen anorexics, and groups that present security issues, for example, hate groups. Isolation is also a potential problem. If we self identify too much, then there is less likelihood of exposure to alternative ideas.

Related articles

- Happy 100th Birthday, Ronald Coase, Nobel-winning Economist & Pathbreaking FCC Critic! (reason.com)

- The Good Sense of Ronald Coase (thinkmarkets.wordpress.com)

- Demsetz On Coase and Pigou (cafehayek.com)

Frumkin On Being Nonprofit

Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia |

Change in Net Worth - U.S. Households & Nonprofits |

Peter Frumkin's On Being Nonprofit: A Conceptual and Policy Primer (Harvard University Press, 2005) is, as its title states, a primer on the nonprofit sector. It explores what Frumkin describes as the four important functions that define nonprofits—delivering needed services, promoting civic engagement, expressing values and/or faith, and channeling entrepreneurial activities. The book also looks at the interconnectedness of the nonprofit, business, and government sectors. It explores some facets of public funding, politics, nonprofit missions, and the tendency toward increasing commercialism. This book provides a good general guide for nonprofit practitioners as well as explores many aspects of the nonprofit sector.

Frumkin divides the purposes of nonprofits into four functions:

- Promoting civic and political engagement,

- Delivering critical services within communities,

- Providing an institutional vehicle for social entrepreneurship, and

- Allowing the expression of values and faith.

The book looks at problems within each of these four functional realms as well as nonprofits' competitions and collaborations with the private sector and government. The problems of nonprofits include politicization, vendorism, commercialism, and particularism. The successes of nonprofits demand commitment to expression, engagement, entrepreneurship, and service. Balancing nonprofits' four functions while overcoming these challenges enable nonprofits to gain support and acceptance. The survival of nonprofits depends on the quality and relevance of each to its mission and its capacity to deliver value.

Peter Frumkin |

Frumkin succinctly defines the nonprofit sector as “the contested arena between the state and the market where public and private concerns meet and where individual and social efforts are united.” (p. 7)

Over time, he explains that the boundaries between the public, private, and nonprofit spheres have changed and evolved. Nonprofits have contributed to democratization by opening societies and giving voice and collective expression opportunities to their constituents.

The main types of nonprofits (and their primary funding bases) are described as follows:

- Hospitals (fee-based, stable and long-term)

- Universities (tuition-based, stable, and long-term)

- Mentoring programs (charitable contributions, fragile and transient)

- Service organizations (e.g. elderly, poor, often rely on government funding)

- Arts organizations (charitable contributions)

- Licensing bodies (fee-based)

- Private member organizations (non public funding)

- Religious organizations (non public funding, stable and long term)

Frumkin lists the three defining features of nonprofits as follows:

- They do not coerce participation (most fundamental feature, depends on good will, increases trust, moral “high ground”, closer to market than government),

- They operate without distributing profits to shareholders, and

- They do not have simple and clear lines of ownership and accountability.

These features can either make nonprofits weak, inefficient, and direction-less or, more likely, they give nonprofits unique advantages over other organizational types. They enable nonprofits to service niches not addressed by the private sector or government.

Frumkin goes on to explore the politics of nonprofits and the motivations of nonprofits. He sees some nonprofits as (generally) liberal –leaning (i.e., people willing to toil in low paying or voluntary positions, self-selected group that consist of untainted partners of government, and many political activists) or right-leaning (i.e., faith-based organizations, organizations promoting self-help and independence, and innovation factories). Perhaps, however, this definition is more motivational than political. In other words, some nonprofits are demand- or supply-side driven. Demand-side nonprofits rely on the the instrumental character of their outcomes (obligations); supply-side nonprofits depend on the expressive quality of their activities. Ultimately, Frumkin sees elements of both in many nonprofits, but he sees nonprofits' tradeoffs with respect to equality and efficiency as their central challenge.

Related articles

- IRS Definition of a Nonprofit Corporation (thinkup.waldenu.edu)

- Tom Sheridan: Nonprofits Must Stand Up and Fight for Themselves, or Perish (huffingtonpost.com)

Wolf on Managing a Nonprofit Organization

Thomas Wolf's book, Managing a Nonprofit Organization in the Twenty-first Century (Third Edition, Simon and Schuster, 1999), is an encyclopedic primer on nonprofit management that explains how to deal with organizational growth and change and that describes the challenges of working with volunteers, staff, and trustees. This book also deals with the emergence of profit-oriented ventures, changes in accounting rules, customer-orientation, and the role of leadership in nonprofit management. From the point of view of the nonprofit practictioner, perhaps the most useful aspect of this book is its very helpful checklists at the end of each chapter.

The author wrote this book because (1) he was concerned about the sustainability of nonprofits, (2) he wanted to articulate the difference between the nonprofit and for profit sectors, and (3) he wanted to address issues related to nonprofit leadership development and maintenance.

Wolf starts by describing what nonprofts are. This includes:

- A collection of over 1 million organizations in the U.S.

- Organizationsa that range from small-budget grassroots organizations to universities with endowments in the billions of dollars

- Five percent of all U.S, institutions and two percent of all U.S. assets

- An employer of 15 million in the U.S.

- A sector whose value is $200 billion annually (in 2000 dollars)

- Ultimately, however, he concludes that there is no easy answer to "What is a nonprofit?" since this question has many forms of an answer. Managing a nonprofit is more nebulous than the profit sector since the purpose is public service, measuring success or failure is challenging, and a nonprofit has no owner.

The defining characteristics of nonprofits include:

- They are established to provide a public service (with a few exceptions, e.g., clubs, unions, condo associations). They may provide services that are also provided by private sector (e.g., education, health services)—although they have no mandate of equity

- Their governance must preclude self-interest and private gain

- They are exempt from taxation

- Gifts to them are tax deductible

- Articulating a mission

- Engaging in risk/survival analysis

- Identifying/involving a constituency

- Testing for "organized abandonment" (i.e., at what point, if any, has the mission been accomplished and/or is the nonprofit no longer relevant?) This point, in particular, is interesting because it seems more theoretical than real since, in actuality, most nonprofits would simply adjust their missions rather than close (assuming they still have funds and/or funding sources).

Wolf also recognizes that, while the board is essential for organizing the nonprofit, it cannot effectively fulfill its job without information, help, and support from its executive director. It is essential for the executive director to have a good relationship with the board by supporting their operations and administration. The following are responsibilities that the executive director has to the board:

- Maintaining structure by sending out notices, providing agenda, and coordinating meetings.

- Respecting them and facilitating discussion on important topics relevant to meetings and structure of a nonprofit.

- Keeping them informed of decisions and changes.

- Making sure he/she is not dominating the board and letting the board do their job effectively without too much intervention.

In addition, Wolf also addresses fundraising, planning, and managing information in nonprofits. His book provides a comprehensive overview of nonprofits and nonprofit management.

Related articles

- Nonprofit Organization Start Up and Compliance (bjconquest.com)

- How to Create an Effective Non-Profit Mission Statement (crystalkeyministries.wordpress.com)

- Nonprofit Consulting Essentials: Management & Governance Consulting (forgrantwritersonly.com)

- Professionalism in Nonprofit Technology: Should My Techies be Accidental? (nten.org)

- Bringing a Network Mindset To Nonprofit Boards (bethkanter.org)

- Better Fundraising for Small Nonprofits (thenon-profittoolbox.com)

Glaeser on Nonprofit Governance

Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia |

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC |

Edward Glaeser’s book, The Governance of Not-for-Profit Organizations: National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report (University of Chicago Press, 2006), explores the pressures and challenges affecting nonprofit governance. Glaeser starts his book by asking, “What makes nonprofits different?” He answers that nonprofits have (1) tax privileges, (2) nondistribution constraints (i.e., they cannot distribute profits), and (3) no owners. He observes that these unique features give nonprofits boards and CEOs unmatched autonomy. Interestingly, though, this observation isn’t his main contribution. Instead, he believes that nonprofits’ workers can also determine their firms’ preferences.

Edward Glaeser |

Glaeser presents nonprofits in a model consisting of four types of actors—managers (the CEO and board of the nonprofit), workers, donors, and customers. The role of the managers is to determine the nature of the production of the nonprofit, the workers carry out the production for the benefit of the customers, and donors provide the financing to enable these activities. Glaeser’s thesis is that, because of weak incentives, nonprofits tend (usually) to orient their production and its details towards the interests of their workers. Nonprofit managers' main motivation is prevention of embarrassment (which replaces maximization of profit in for profit firms). Since workers are in the best position (usually) to cause embarrassment, the tendency toward satisfying workers is natural. The book’s contributors look at four types of nonprofit operations—hospitals (doctors), art museums (curators), academia (professors), and the Catholic Church (priests)—from aspects ranging from fundraising to endowments to specific governance issues. The overall picture that presents itself is one of a complex range of governance problems and observations—everything from nonprofits that maximize their employees’ interests to nonprofits that closely mirror their stated missions. Thus, nonprofit government becomes a balancing act that must incorporate the interests of all four classes of actors. Overall, the book is an interesting, challenging read.

Related articles

- Book Review: 'Triumph of the City' (businessweek.com)

- Triumph of the City, By Edward Glaeser (independent.co.uk)

- Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier (newstatesman.com)

- EDWARD GLAESER: The Country Needs to Unleash Entrepreneurs (lexingtonva.wordpress.com)

- A Conversation With Edward L. Glaeser (economix.blogs.nytimes.com)

Peter Drucker on Management and, in Particular, Nonprofit Management

In The End of Economic Man: The Origins of Totalitarianism (1939), Peter F. Drucker argued that capitalism can generate economic development, but he believed that capitalism was bad as a underlying social system due to its "failure to establish equality by economic freedom." Drucker believed this is why the Germans and Russians chose socialism (although this was an ideology that Drucker thought was both totalitarian and of little value) in the early 20th century.

Drucker, instead, saw early 20th century American corporations as a source for a potential alternative. Corporations such as General Motors had become excellent at wealth creation. Drucker believed that such firms could also help provide a sense of community to their managers and employees. He wanted these firms to develop health and pension plans, to involve employees in corporate governance, and to build factories closer to where people lived. He believed that profits should not be the only goal of economic life, but rather an indicator of how businesses were doing in motivating their workers to produce goods and services. (Drucker perhaps failed to realize the full implications of the fact that corporations would chase lower production costs to other jurisdictions (and sets of values influenced by their current, less fully developed economic conditions) as the costs of creating the "sense of community" at home accrued.) This book set the stage for Drucker's outlook on businesses (and nonprofits) for the remainder of his life.

In 1990, Drucker wrote a guidebook for and about nonprofits, Managing the Non-Profit Organization: Principles and Practices (Collins, 1992). Drucker was interested in nonprofit groups because he thought they played a key role in giving a purpose to modern societies, a task he felt that, despite their economic successes, businesses increasingly avoided. Drucker meant this book as advice for leaders in the "social sector." He saw nonprofits as an American innovation that built communities while providing valuable services and fostering innovation and as leaders in knowledge-driven economic activity. However, he also thought that nonprofits had plenty of room for improvement, and his book emphasized working on development of the mission and governance of nonprofits. His hope to improve the performance of nonprofits, and his recognition that without nonprofits their great contribution to social equality would disappear, spurred his efforts in this area.

Drucker's book is well organized and emphasizes the nonprofit mission and governance. He divides the book into the following chapters:

- Mission comes first and the role of a leader

- From mission to performance: effective strategies for marketing, innovation, and development

- Managing for performance

- People and relationships: staff, board volunteers, and community

- Developing yourself: as a person, executive, or leader

Drucker felt that donors needed to feel more like participants and to learn how to offer volunteers a greater sense of "community and common purpose." According to Drucker, management is about goals, not processes, habits, and rules.

Related articles

- Druckerism (linusfernandes.com)

- "Until we can manage time, we can manage nothing else." Peter Drucker (3dimensionallife.wordpress.com)

- Drucker on the PMP (yahooeysblog.wordpress.com)

- Is it possible to be a leader? (berfulogia.wordpress.com)

Monday, March 28, 2011

Climate Change and Discount Rates

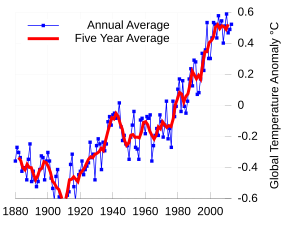

Image via Wikipedia Image via Wikipedia |

| Global Mean Surface Temperature Difference Data |

Many analysts have observed that the range of the expected future impacts of anthropogenic climate change is highly dependent upon discount rates. Depending upon the time horizon and discount rate selected, one can derive almost any desired outcome. Given this observation, it is crucial that one carefully consider and document one’s reasoning related to choice of discount rate and time horizon when attempting to make credible, defensible climate change projections.

In most benefit-cost analyses (BCA), the application of discount rates to the proposed project’s entire life-cycle costs versus alternative uses for its proposed investment calculates the net present values of the cost and benefit flows of the project and its cash flows[i] versus alternative “risk free” uses of capital[ii]. When the net present value of the project exceeds alternative uses, the project is deemed feasible.

There are at least three methods for determining the discount rate that can be selected—the opportunity cost method, the social time preference method, and the intergenerational method. Often, public sector officials evaluate investments by using the opportunity cost method. In this method, discount rates are based upon market rates[iii] in order to avoid crowding out private sector investments. The actual numbers used are often determined based on investment advisors’ surveys of market rates. Discount rates selected by this method, if not carefully calibrated, do not adjust for externalities such as the costs of pollution, rising global temperatures, and market power dynamics such as monopolies. Thus, this type of discount rate is usually inappropriate in climate change modeling.

Another, more appropriate method of discounting is by social time preference discounting. This concept of discounting arises from the observation that people prefer immediate to deferred satisfaction. The compensation (or increased utility) that a person (or group) requires in order to defer immediate consumption is measured. The discount rate is the percentage measure of this compensation per unit time. This rate is largely a measure of the pure rate of time preference, but it also has implicit elements of relative risk aversion (i.e., the uncertainty in climate change estimates) and of consumption growth rates (i.e., correlated variables that drive the variables which slow or quicken the speed and direction of climate change). By addressing many timing and input uncertainties and the asymmetry of drivers and impacts, social time preference discounting is an improvement over opportunity cost discounting.

A third, more controversial method of discounting is the intergenerational method. It can be argued on an ethical basis that there should be no preference between the value of a benefit (or cost) now and the same benefit (or cost) in the future after allowing for the expected probability of the extinction of human beings, such that an intergenerational discount rate might be about 0.1 percent per annum[iv].

[i] That include allowances for risk by using a “risk free” discount rate (such as T-bills) or by using probability ranges to calculate ranges of net present expected values.

[ii] The proxy for this is simulating an investment in a risk-free investment such as Treasury bills in an allocation whose maturities correspond with the project’s expected life cycle.

[iii] Social discount rate and liquidity preference (i.e., one’s asset preference distribution (wherein the distribution is by their ability to be easily transferred—i.e., cash is the most liquid of assets)) largely determine market interest rates. Market interest rates can also be thought of as the discount rate for appraisal of an investment or the cost of capital to the investor with a risk adjustment. Cost of capital can be calculated as the weighted average of its cost of equity and debt, with the proportion of debt is limited by the risk of insolvency.

[iv] This might also be viewed as the most extreme social time preference method.

Related articles

- What's the cost of climate change? Pick a number. (wwwp.dailyclimate.org)

- What is the economic cost of climate change? (guardian.co.uk)

- Ethical dilemma profoundly sways climate economics. (wwwp.dailyclimate.org)

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Climategate as Sloppy Reporting and Wishful Thinking

A fascinating video that largely debunks Climategate.

Sunday, January 23, 2011

Jobs Guru?

Obama has made a poor choice of Jeffrey Immelt as his "Jobs' Guru," also known as head of the Council on Jobs and Competitiveness (a new group that replaces the Economic Recovery Advisory Board).

Immelt has said, “It should be our goal [to restore the 2 million jobs lost in the recent recession].... Restoring manufacturing might to this country should be a high priority. Because they pull a lot of jobs with them; big companies and small companies work together; the best way to create high-value middle-class jobs is through manufacturing. So I think it should be a high priority.”

During his tenure as GE's CEO (based on an examination of GE's 2000 and 2009 Annual Reports), Immelt has grown GE's U.S. jobs by about 3000 overall or an anemic 0.25% per year. On the positive side, he has helped create 81,000 non-U.S. jobs, a healthy 4.25% per annum pace.

During his tenure as GE's CEO (based on an examination of GE's 2000 and 2009 Annual Reports), Immelt has grown GE's U.S. jobs by about 3000 overall or an anemic 0.25% per year. On the positive side, he has helped create 81,000 non-U.S. jobs, a healthy 4.25% per annum pace.

What he says and what he does don't jibe. Well, they could jibe if you decrease U.S. labor costs to meet those of Asia... .

Immelt has said, “It should be our goal [to restore the 2 million jobs lost in the recent recession].... Restoring manufacturing might to this country should be a high priority. Because they pull a lot of jobs with them; big companies and small companies work together; the best way to create high-value middle-class jobs is through manufacturing. So I think it should be a high priority.”

During his tenure as GE's CEO (based on an examination of GE's 2000 and 2009 Annual Reports), Immelt has grown GE's U.S. jobs by about 3000 overall or an anemic 0.25% per year. On the positive side, he has helped create 81,000 non-U.S. jobs, a healthy 4.25% per annum pace.

During his tenure as GE's CEO (based on an examination of GE's 2000 and 2009 Annual Reports), Immelt has grown GE's U.S. jobs by about 3000 overall or an anemic 0.25% per year. On the positive side, he has helped create 81,000 non-U.S. jobs, a healthy 4.25% per annum pace.What he says and what he does don't jibe. Well, they could jibe if you decrease U.S. labor costs to meet those of Asia... .

Related articles

- Jeffrey Immelt 101 (economix.blogs.nytimes.com)

- ""Trustee Jeffrey Immelt '78 Appointed to an Additional Prestigious Position" and related posts (dartblog.com)

- Jeffrey Immelt to Lead a 'Jobs Committee'? (redstate.com)

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Copyright and Fair Use

The video, A Fair(y) Use Tale, was created in 2007 by Eric Faden of Bucknell University to illustrate key concepts of U.S. copyright law. It uses short clips from copyrighted Disney movies.

Monday, September 6, 2010

Modeling, Simulation, and Games Research

"The technical and cultural boundaries between modeling, simulation, and games are increasingly blurring, providing broader access to capabilities in modeling and simulation and further credibility to game-based applications. The purpose of ... [following] study is to provide a technical assessment of Modeling, Simulation, and Games (MS&G) research and development worldwide and to identify future applications of this technology and its potential impacts on government and society. Further, this study identifies feasible applications of gaming and simulation for military systems; associated vulnerabilities of, risks to, and impacts on critical defense capabilities; and other significant indicators and warnings that can help prevent or mitigate surprises related to technology applications by those with hostile intent. Finally, this book recommends priorities for future action by appropriate departments of the intelligence community, the Department of Defense research community, and other government entities."

Average Total Compensation for All California Cities' Municipal Workers

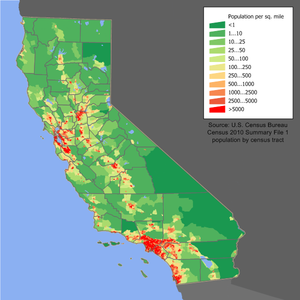

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaRecently, I decided to calculate the total compensation of California's city public sector employees by city and rank them. The results are interesting.

A table sorted by compensation follows :

Related articles by Zemanta

- Salary of $800,000 Sparks California Taxpayer Mutiny: Joe Mysak (businessweek.com)

- Robert Rizzo's Salary Package Topped $1.5 Million (huffingtonpost.com)

- Excessive Bell salaries prompt bills in California (sfgate.com)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)